The Future of (Out of) Work

What a modern Unemployment Insurance system could look like

My last post detailed Unemployment Insurance’s many failings and why the system won’t right itself. What should a new one look like? Where do we start?

There’s two ways to approach it. One is to start from the current program, take the good and leave the bad. The other is to start from the current problem that program needs to address, and then work back to the solution. Ideally, they meet in the same place.

Let’s do both, starting with the current program.

The Good and the Bad of Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment insurance is a social insurance program. Benefits are financed through a payroll tax whose contributions are deposited into a trust fund. Workers gain coverage through those taxes. If they become unemployed, they can file a claim for benefits. The size of the benefit is a function of their past earnings.

All this is great. Social insurance programs have a broad tax base and dedicated funding. Keeping it off the table for annual Congressional spending (when they dole out spending from income tax revenue) helps with the continuity of benefits and stability of the program. Plus, unemployment is a cyclical issue—it’s more likely during recessions—so that unemployment insurance is also cyclical—it’s more expensive during recessions. Rather than squeeze budgets at a difficult economic time, the trust fund saves up over boom times.

Social insurance programs also aren’t means tested, but situation tested. To get a benefit like food stamps, you have to prove that you are very low income. For unemployment, you don’t have to be low income, you just have to be unemployed through no fault of your own with a sufficient work history. The benefit isn’t set at a dollar amount, but a replacement rate—some fraction of your past earnings. This ensures that there’s broad support from the program, not just for very low earners.

And America really likes social insurance programs. Social Security is the shining example. We all pay in, we all get out, and merit is based on work, not need. There’s deservedness that comes from paying in.

Unemployment insurance is a social insurance program and should stay that way. That’s the good. The bad is almost everything else.

I’ll sum up here, but you can read a more thorough discussion in my last post:

Bad 1: Tax payer. In the current system, only the employer pays the payroll tax, not the worker (except in a couple states). Employers are financing a program that they don’t directly benefit from, so they have no incentive to keep the program in good financial shape or keep benefits generous. Indeed, the better the program, the more it cost them. This is bad design.

(I wrote about this in the New York Times a couple of years ago).

Bad 2: Tax setter. Unemployment insurance is not a single program but a confederation of 53 separate programs. Individual state legislatures set the tax rates and benefits for their state. States who are competing for firms to locate in their state are pushed into a race-to-the-bottom for taxes, including payroll taxes. Again, this is bad design because again, these states have less incentive to keep the program in good financial shape or keep benefits generous.

Bad 3: Tax coverage. Because unemployment payroll taxes are only paid by employers, independent contractors are completely excluded from the system. This is another way the state-run system hits hard. Not all states have income taxes, so they don’t all have the same mechanisms or administration to have independent contractors pay into the program.

Bad 4: Tax structure. This is the worst one! This is the lede, buried! Unemployment payroll taxes are experience rated. Firms have a base rate they pay on every employee, but the more former employees who are laid off and get benefits, the higher the tax on all current and future employees. This was meant to be a feature, the program was designed to prevent and discourage layoff. How do you discourage something? Tax it! Unemployment was designed as a layoff tax. It’s a powerful incentive but it didn’t land where they wanted it to, because instead of discouraging layoffs it really serves as a way to discourage people from claiming benefits.

(You can read more about the business behind reducing claims here. The company the article is about, Talx, was acquired by Equifax and renamed Equifax Workforce Solutions. They are a little less brazen than they used to be; their home page previously featured statistics of how much less in claims are paid to workers when businesses use their service.)

Bad 5: Benefit amount. I put this fifth, and not first, because benefit generosity reflects all the bad financing issues, rather than dictating them. Benefit amounts are also set by state legislatures, they vary widely and wildly across states, and they’ve eroded over time. Given the incentives built into the financing, their erosion is a logical result.

(Varying by state also has some nasty consequences. I wrote about this during the first pandemic summer: states with the lowest benefits tend to have high shares of black workers. It was then picked up by the New York Times.)

What do we learn from these five bads? Unemployment insurance needs to be a federal program, with a uniform payroll tax across all states, all firms, and all employment arrangements, including independent contractors, and a uniform benefit design.

We’re halfway there. Now let’s go to the problem.

The Good and The Bad of the US Labor Market

Forgot the current rules and eligibility. The idea of unemployment insurance, as the name suggests, is to meet the risk of job loss that is inherent to the labor market, but out of the control of any individual worker. That risk is rather breathtaking when you think about it: Recessions, automation, technological change, banking crises, stock bubbles, real estate bubbles, offshoring, outsourcing, pandemics, executive mismanagement, downsizing, natural disasters, and, new to the group, artificial intelligence.

This is design note 1: There are lots of ways for workers to lose their job that is out of their control, and those ways are always evolving. There is no eradicating labor market risk. It’s a hydra, cut off one head and another will emerge.

Job loss doesn’t have the same effect on everyone. It depends on a lot of things, most importantly the nature of the loss. Think of a typist starting their career in the 1950s. Over the ensuing decades, they might have lost a few jobs when the economy was bad, or when their employer was struggling and needed to cut back. But at some point, their employer was fine, they just didn’t need a typist anymore. Sometimes workers lose a job, sometimes they lose a career.

Another way to think about this is to think of the market for a worker’s skill. Some skills see their market value fall so much they are practically eliminated from the labor market. Typing used to be a unique skill with little substitution, now it’s neither.

Design note 2: There are many different types of unemployment, based on the nature of job loss.

What are the effects on workers for whom that risk is realized? Some workers will be able to bounce back from a job loss and get quickly reabsorbed back into the labor market, others won’t. The biggest factor in reemployment is the overall unemployment rate; it’s hard to find a job when there are fewer of them to go around. The Great Recession (which earned its title!) was marked by very long unemployment spells, but as many people pointed out at the time, the primary distinguishing feature of the long-term unemployed was their terrible timing in when they first lost their job. Not only can it be out of your control if you lose your job, it can be out of your control how hard it is to get another one.

Design note 3: Recovery from job loss depends on the overall economy.

It’s important to stop here and think about what that means, not solely for designing policy, but in how we think of ‘the unemployed’ as a group. To accept that job loss and recovery are out of a worker’s control is much harder than it sounds, because it requires acknowledging that you, yourself, could lose your job and not find one.

Take the self assured logic: I work hard and make good decisions, therefore I will keep my job. Seems harmless, until you inverse it in order to apply it to the unemployed: they lost their job, therefore they did not work hard or make good decisions.

A need for assurance in our own position can make us cruel towards others less lucky. It’s why the unemployed are often described as lazy, and the unemployed on benefits as lazy and entitled, though rarely in those exact words. It’s tough and even a little scary to admit you could work hard and still lose, so when you see someone lose, it’s easier to assume they just didn’t try hard. Easier for you, that is.

This view of the unemployed goes deep. A few years ago I read a book about the eruption of Mount St Helens. The mountain shook and bulged for over a month before the eruption. Volcanoes often do that before they erupt. They also sometimes do that and don’t erupt. This led to a lot of dispute at the time about how much precaution to take. The state set up zones that restricted where people could or could not go, the red zone being the most dangerous. The public was not allowed in the red zone, but workers for the logging company were. They started calling a field office of the state’s Industrial Safety and Health agency, complaining that it wasn’t safe to work on the mountain. And what did he say?

“I thought that most of the complaints were from people who wanted a way to get out of work. Frankly, I thought they were out to get unemployment [compensation]. Now, I wouldn’t want this to get out in the press, but that’s what I thought.”

The unemployed don’t have a way to counter this rhetoric that they are lazy takers. Unemployment is a temporary state, meaning the unemployed aren’t a permanent constituency. An ever changing group of workers who fall in and fall right back out of membership doesn’t facilitate representative advocacy. Consider the AARP. Once you turn 65, you stay over 65, allowing the AARP able to draw on a permanent group of people for support in exchange for lobbying and working on their behalf. Unemployment is a tough financial time and also temporary; an AARP for the unemployed isn’t viable in terms of resources or identity.

Policy design doesn’t happen in a bubble. How people view the unemployed and how people view beneficiaries has to be front of mind.

Design note 4: The unemployed are not well liked or respected; most are considered lazy.

The last part of the problem is that that unemployment in our economy is changing in certain ways. Quick definition: A worker is unemployed if they do not have a job but are actively looking for work. Search distinguishes a worker who is out of the job from someone who doesn’t want one, like a student or a retiree. Because the US has an exceptional statistical agency in the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we know a lot about unemployment and how it’s changed over time.

For example, unemployment spikes in recessions. The time between recessions is growing since the 1950s, but the unemployment rate during recessions is getting higher and is taking longer to fall (see the Great Recession starting in 2007).

Workers today stay unemployed longer. You can see this in looking at the average and median duration of any given spell. The average spell has increased from around 10 weeks to closer to 25. The median has also increased, from around 5 weeks to around 10; half of all spells are shorter than 10 weeks.

But the entry into unemployment has not changed much. There are three ways to ways to enter unemployment: lose your job, leave your job, or start to search for a job.

About 50% of the unemployed at any given time have lost a job, though that share increases during recessions. About 30% are re-entrants to the labor force, meaning they have worked before but have not been working or looking for some time. A classic example of re-entrant is a mom who left work to stay at home with kids while they were young, and then went back to work when they started kindergarten. When she starts looking, she’s a re-entrant. Another 10% are job leavers, who quit their job to find a new one, and a final 10% are new entrants, like recent graduates, who are searching for their first job.

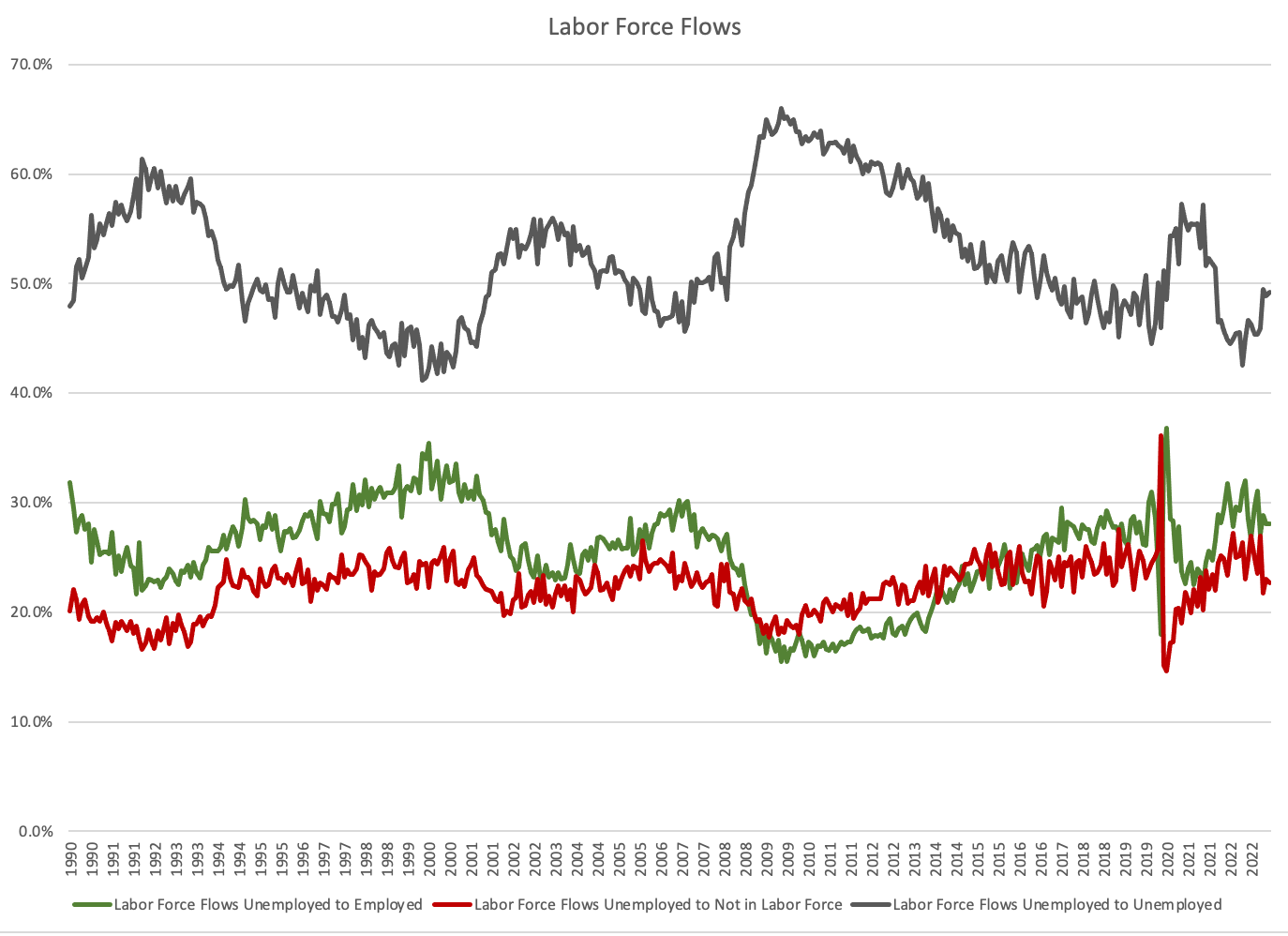

The exit has also not changed much (but the data only goes back to 1990). Take all the workers who are unemployed in one month and then check next month whether they are either still unemployed, employed, or out of the labor force. These are called labor force flows.

In any given month, about half of the unemployed will be unemployed the following month. This varies with recessions, when the share staying unemployed gets higher. Otherwise, its equal attrition into employment or out of the labor force.

(The flows out of the labor force are a little hard to interpret, because in order to remain unemployed, a worker has to have looked for work in the past four weeks. Say you take a month off from putting in new applications because you are waiting to hear back from other places, or there aren’t any new jobs posted for you, and whooosh, you’ve fallen out of the labor force because you no longer meet the technical definition, but your situation hasn’t really changed. If you look at the flows into employment—starting a job when you didn’t have one the month before—about twice as many people come from out of the labor force than they do unemployment.)

Design note 5: Unemployment is cyclical, it’s lasting longer, about half of the unemployed are job losers, and they mostly get jobs again.

Putting it all together

So where does Unemployment Insurance fit in all of this, or where should it? We know from the current program that the next one needs to be federal, with uniform taxes and uniform benefits across states that everyone pays into—firm, contractor, employer, employee alike. And we know from the current problem that people lose jobs, this can be hard to recover from if the economy is bad or if its tantamount to a career loss, but either way, they won’t be liked or trusted.

The answer is to make the program eligible to more people so that it becomes viewed as a broadly shared and earned investment, rather than a targeted subsidy. At the same time, the program needs to target subsidies to those who are experiencing the worst loss at the worst time. These aren’t incompatible if the program is triaged.

In this new program, benefits have tiers. Each tier has a different replacement rate, different length, and different level of service provision.

Tier one - open for the churn. The first tier of benefits are relatively generous, but very very short. Think 70% replacement but for 2 weeks. Workers had to have been working to be eligible, but there’s little causal eligibility aside from that. It’s an open benefit for people not working, including if they quit. Since there’s fewer eligibility tests, workers could get the benefit as a one-time payment or series of payments.

This fundamentally changes who gets the program—now if you quit to go to school, or move across the country, or stay home to caregive for sick or newborn family members—you get a small quit bonus. It’s not just for the unlucky (read: viewed as lazy) job losers. You could think of this first tier as akin to a worker savings account that they can use as needed (not repeatedly, I’ll get to that).

It also is a small boost towards worker power. Employers in the US hold incredible power over the labor market in the form of monopsony, pushing down overall wages by as much as 20%. Giving workers a subsidy to search without having to get laid off first helps tip the scale in a small but meaningful way.

Tier two - in some trouble. The second tier of benefits are less generous and last longer. Think 60% replacement for 8 weeks. It’s intended for workers who will need some time and help to find a job. In order to transition from tier one to tier two, a worker has to reapply and meet with an employment counselor. An employment counselor is a few steps down from caseworker, but still meets with the worker over a few sessions and talks about the labor market, jobs, their skills, their goals. The current iteration of unemployment insurance has RESEA, reemployment services and eligibility assessments. It’s shown to be very effective at helping workers find jobs.

Eligibility at tier two is difficult to design. Who should get these benefits? Traditional gatekeeping for unemployment insurance has been held by the employer—they tell state workforce agencies whether the worker lost the job for cause or not. This is a worthiness test, a way to direct benefits to “good workers” and away from “bad workers.” Since in the current system, employers get taxed more if a worker enrolls in unemployment, they have an incentive to verify and take on this administrative hurdle. If that tax incentive goes away (it must must must must must must go away), should employers have a say in who gets unemployment?

I’m tempted to say, workers who apply for tier two benefits have to get some kind of note or reference or verification from their former employer, not as strict as the current “let go, not for cause” requirement, but some acknowledgement that the worker was not very bad at their job.

Yet, I can’t imagine a world in which that doesn’t turn out badly for black workers. A key fact in our labor market is that black workers are discriminated against. It’s not conjecture, but repeatedly proven. A program that pretends discrimination doesn’t exist will contribute to it. And since discretion breeds discrimination, giving former employers a say over employees will without a doubt put black workers in a worse place.

And consider too that wherever there are women workers, there is the potential for sexual harassment, which is both widespread in the labor market while concentrated in certain industries. Most complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission regarding sexual harassment are not just the harassment, but retaliation for reporting it. Workers have so internalized that they will be punished for speaking up about sexual harassment that they do it less when the unemployment rate is high and it would be harder to find another job. (The same study found that they also do it less when unemployment benefits are ungenerous.)

That’s the tradeoff of having an employer-administered worthiness test. No test: a bad worker could get unemployment. Test: employers’ discretion enables discrimination and retaliation.

I think the current system’s aversion to helping “bad workers” is misidentified. Not being fired for cause is not equivalent to being good at your job. And it’s uneven, because it doesn’t allow for a parallel worker assessment of “bad employers” for their former jobs. Amazon could fire someone for peeing in a bottle while driving and then that worker wouldn’t get unemployment, even though peeing in a bottle is a result of Amazon not scheduling bathroom breaks or providing bathrooms, in violation of labor law. Performance is a two-way street.

But even if “bad workers” were perfectly identified, that aversion to helping them would still be misplaced. It perpetuates the idea that unemployment benefits are a reward that has to be reserved for the few, instead of part of a system to help workers get reemployed. Some people need time, some need services, some people need education, some people need training. As scary as the implication can be for eligibility, all of those goals are impeded by an employer worthiness test that arbitrarily limits services.

Eligibility at tier two would have to be nearly as open as tier one, but with the requirement that they have to reapply and there’s an employment counselor screener. Weekly recertification through proof of job search can be added in tier two as well.

Tier three - in more trouble. Tier three would see a similar step down in benefit amounts, think 40% replacement, for another stretch of weeks, say 12. Tier three would require regular employment counseling in a role getting closer to caseworker. These workers are now past the median in unemployment spell length.

It’s important for the new system to break up the typical six months of benefits that workers currently get into two separate stints. Prior research has shown that the expiration of benefits changes worker employment and search behavior. Workers tend to take a job right as their benefits end, or if they don’t get a job, leave the labor force as their benefits end. Benefit timing and length will absolutely affect employment and search behavior, so we should design the program to take that into account. Benefit decreases would accelerate job taking, while additional counseling would help maintain labor force attachment.

Tier four - in transition. At some point, a worker may decide that they need to go back to school or get training in order to get a job. Or they may decide they’d be better off starting a business rather than looking for work. Or they need to move to another labor market and search there. Tier four benefits would be an even lower replacement but for a period of time that supports these transitions rather than a predetermined, uniform length. A worker could switch to tier four at any point (i.e. don’t have to wait 20 weeks to start) and could potentially cash out part of the skipped or accelerated tiers. This last tier is geared for the job loss that’s career loss.

A more open eligibility unemployment system has the potential to buckle at the seams if there is no cap to benefits. Progression through the tiers would have to be on a rolling window, something like ten years, so that if you keep getting unemployed, you get a lower benefit each time and more service provision. Tier one benefits would be something workers could claim no more than once a decade.

In recessions, all of these things—tier replacement rates, tier lengths, rolling windows—could all be relaxed or increased. Similarly in periods of full employment, they could all be tightened or decreased.

Why are we doing this

I was at a research conference recently in which authors presented their new, unpublished results on unemployment insurance. One person found that more generous benefits delayed job starting by about a week. Another person found that increases to unemployment led to higher reported trust and support in government among the unemployed, a milestone considering how low trust in government is.

My comments in discussing these papers is that we’ve never decided what unemployment is for.

If the goal is to get people back to work as quickly as possible, then the best unemployment program is no program at all. That risks poverty, foreclosure, economic ruin of families and communities, and a share of the workforce churning through low-wage jobs with no upward mobility or security. It also risks swelling participation in programs that are means tested, like SNAP and Medicaid, and intended for long-term nonworkers, like SSI. Given how low unemployment benefits are and how few people get them, we aren’t far from this world, especially in states slashing their unemployment program.

The jobs that are traditionally the quickest to get are entry level in the low-wage service sector. There’s not a lot of good that pooling more and more workers into those jobs will get us, or any issues in our labor market it would solve. Human capital and the investments we’ve made in the skills, education, and experience of workers is really valuable. Employers know it. Read any news article about the labor market over the past two years and you’ll read about worker shortages or about workers not having the right skill. Policymakers know it too. That’s why the CHIPS and Science Act has money for worker training, as did the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act and the America COMPETES Act.

Getting people back to work as quickly as possible is not a good goal. Heresy! I know. But its unbalanced and shortsighted. Maximizing human capital recovery after job loss is a goal that is balanced, forward looking, and really hard. But part of what makes it hard is that we’ve never really tried, not in earnest. The average unemployment spell is around 25 weeks. The typical length of unemployment insurance benefits is 26 weeks. We can do more than give a fraction of the unemployed a fixed duration of cash and hope that everyone hits the average.

I think back a lot about the relationship between trust in government as it relates to unemployment, especially as I read story after story about how artificially intelligent chatbots are going to take all our jobs.

What is an unemployment program for?

It’s insurance against the risk of loss, both of income and of relevance, the risk that you are no longer valued by the labor market. Americans deserve for that insurance to be comprehensive.