The Empowerment Trap

Happy New Year, You're Doing it Wrong!

I started off last year with a post—The Hummingbirds—that explains that women’s economic progress has stalled in the face of abject public policy failure, but women internalize the symptoms of that failure as their own personal problem. We are left fighting furiously just to stay still, like a hummingbird in the air.

As many of us think about our New Year’s Resolutions, I want to expand on last year’s post and the empowerment trap many women get snared in.

Women: Try Harder and Be Better

Women: Don’t Try At All?

Symptom vs Disease: The Example of Unilateral Divorce

Empowered To Do What

Women: Try Harder and Be Better

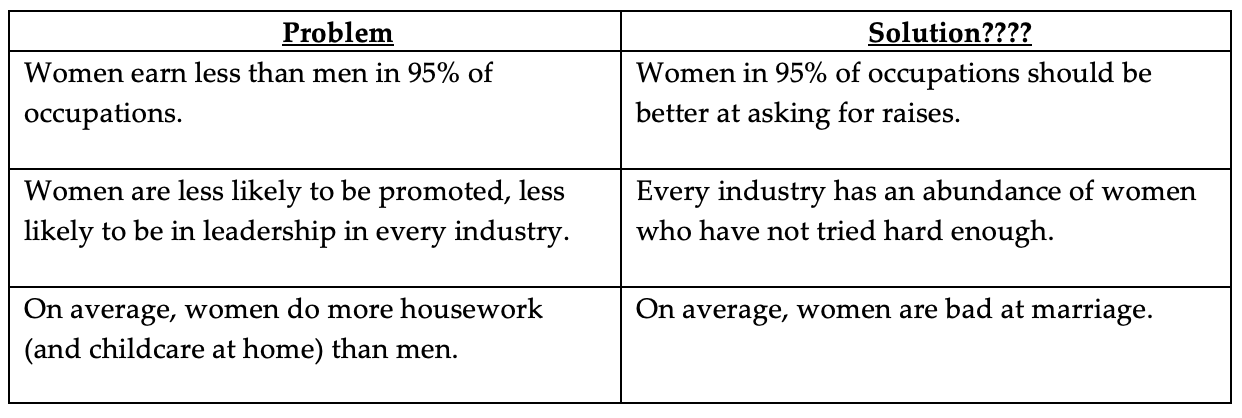

I think and dream in excel, so I’m going to explain the Empowerment Trap in two tables. Starting with: table of things you, as a woman, probably failed to accomplish.

On the left, we have three of the common problems women face in their lives: they want to earn more, get a promotion, but struggle with work-life balance. On the right are the pearls of wisdom that are often offered in response: ask for a raise, lean in, make your husband do more.

Table of things you, as a woman, probably failed to accomplish.

On the surface, it all seems reasonable, even within your reach.

And should you want help, the internet is more than happy to provide you with some advice. Forbes, LinkedIn, The Balance, The New York Times, Clever Girl Finance and probably hundreds of others publish how-to guides on asking for a raise. Sheryl Sandberg has a whole book directing women how to be more assertive at work. Truly, biggest kudos goes to “make your husband do more” for generating internet advice columns from such eclectic sources as How Stuff Works and WikiHow, both of which publish step-by-step pictorial guides in changing household chore allocation.

Is it ironic to have a 15-step process in order to achieve less work? They don’t really say!

But all this advice has an insidious component. Take “ask for more.” It’s basically saying that the problem with your employer is that you haven’t fixed them. Think about it: the notion of asking for more is premised on the fact that you are undervalued by your employer. Your work, contributions, skill, leadership, performance aren’t appropriately reflected in your pay. And you know whose fault that is? Yours!

Same with “make your husband do more.” You haven’t made him better. The onus is on you. That your husband, like your employer, is underperforming is your fault.

“Be ambitious/assertive/lean/etc” is a little more nuanced if no less judgemental. The problem there is that you haven’t made yourself better. Male personality entrenched in power structures has awarded bold aggressive ambition—and you’ve failed to mimic it!

It's remarkable how much becomes your fault, how much it’s just women doing things wrong.

Let’s try this again, but this time, we’ll aggregate individual problems and do the same for the solutions. Our individual problems translate into broader problems quite accurately. Women earn less, are promoted less, and do more housework and childcare (at least in heterosexual partnerships). But the solutions, applied to all women, are ridiculous.

Table of things women do wrong?

Do women earn less than men in nearly all occupations because those women aren’t asking for raises? Obviously not. Are we simply running out of ambitious women so there are few in leadership? Again, no. Are nearly all married hetero women bad at getting their husband to do more? Again, no.

In each case, there is something structural that is acting as a disadvantage to women. The individual advice ignores these structural issues. This is the trap. You internalizing as an individual problem to be solved a structural failing you can’t chance.

Women: Don’t Try At All?

To be fair, advice like “ask for a raise” is often genuine. It’s not given with malice. Women need and/or want help. It could be considered cruel if someone were instead to say, “Actually this is all out of your control and no individual effort will result in meaningful change so you ought to give up. You’re welcome.”

And that’s the tension. Women want to improve their individual circumstances with changed behavior, but women and their behavior aren’t the root of the problem.

I’ll say it again, in special font:

Women and their behavior aren’t the root of the problem.

If it were, then it’s just a matter of choices: that there is some constellation of choices that result in women being equal to men. We just have to choose better—all of us—and voila, done.

Advice like “ask for more” or “lean in” emphasizes individual strategies to help one woman deal with tough circumstances, but in a way, it becomes a get-of-jail-free card for people in power who have the ability to change women’s circumstances. It’s focusing on the symptom, not the disease. The symptom can be helped with changes of behavior, but the disease needs a change to law, or public policy, or employer behavior.

I think an example makes this clear.

Symptom vs Disease: The Example of Unilateral Divorce

It doesn’t matter how unhappy or abusive a marriage was, for a long time in the United States, getting a divorce was very—and intentionally—difficult. To be clear, going through a divorce is still emotionally and financially difficult, but in earlier time periods, getting legally out of a marriage was sometimes near impossible.

For women, it could require their husband’s permission, because both parties had to agree to the divorce for it to be granted. If one partner was at fault, the marriage could be dissolved, but establishing fault was also very—and intentionally—difficult.

Divorce without fault and divorce without partner permission wasn’t standard until 1980, though a few states took even longer to grant it. These two changes are grouped together as Unilateral Divorce because however the law was changed, it had the same effect: one party could leave.

Economists have looked at the outcomes of women in the US before an after they had access to unilateral divorce. Some of the findings are interesting, like married women worked more as a result. Other findings are quite sobering. Access to divorce reduced domestic violence of, homicide of, and suicide of married women. These effects weren’t small. Here’s a quote from the authors’ summary:

“In states that introduced unilateral divorce we find a 8–16 percent decline in female suicide, roughly a 30 percent decline in domestic violence for both men and women, and a 10 percent decline in females murdered by their partners.”

It’s not as if women before 1980 never tried to pick a good husband or tried to make their marriage work or tried to mitigate the triggers of aggressive behavior. They probably did the same thing we do: get advice, make new years resolutions, read self-help columns, and so on. Yet, the bone-chilling statistics on violence, homicide, and suicide make clear that individual behavior can’t achieve the same thing as structural change. In this case, trying to be better at marriage isn’t a substitute for the right to leave one.

Whatever we do as individuals, structural change is necessary.

Empowered To Do What

I think of all this as The Empowerment Trap because women today have so much individual power—rights and agency and opportunities that no generation that came before can claim—that it’s easy to hide society’s failings behind our own choices. It’s not like any of those litany of articles advising women how to ask for raises mention that the US doesn’t have paid family leave, or help for child care, or good labor laws with adequate enforcement funds.

I love empowerment, and being empowered. I’ve reveled in the feeling of taking control over my career, I’ve reveled in the feeling of ignoring my career for the sake of my family, I’ve asked for raises, I’ve gone part-time, I’ve put in work after putting the kids to bed, I’ve given advice, I’ve taken advice, I’ve even purchased tea towels with feminist icons on them.

Embrace the new year, embrace empowerment, but don’t let Congress off the hook. This country’s leaders have long hidden their own failure behind your behavior and choices. No amount of individual empowerment can compare to the structural change we need.

I’ve long had the thought that I’m struggling against systems designed to prevent my success. Thank you for giving me clarity.

Reminds me of the Red Queen's race from Alice in Wonderland:

"Well, in our country," said Alice, still panting a little, "you'd generally get to somewhere else—if you run very fast for a long time, as we've been doing."

"A slow sort of country!" said the Queen. "Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!"