"I am so confused"

The U.S. economy right now, as best as I can explain it

The big headline about the economy last week was that Trump is trying to fire Lisa Cook from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. She sued him in response, and on paper at least, she should win.

The big headline a few weeks before that was that Trump successfully fired Erika McEntarfar from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and slandered her, accusing her of manipulating data for political purposes.

Safe to say: August 2025 was a historically bad month for female PhD economists.

Why is he attacking these people? What’s going on in the economy? Truly, it’s a very confusing time.

The short version is that Trump wants interest rates lowered to boost the economy, but its very much a having-your-cake-and-eating-it-too type of campaign, because he also doesn’t want to admit the economy is in trouble, because then he’d have to admit its his policies causing the trouble.

Confusing, and borderline doublespeak. Hopefully I can explain this. If you can stand it, the easiest way to parse through all this is to understand interest rates.

In this letter:

Up or Down (Or Stay in Place)

Why Right Now is Confusing Part 1: The Actual Economy

Why Right Now is Confusing Part 2: What Trump Says

Coda: There’s Always Hope

Up or Down (Or Stay in Place)

The Federal Reserve is the U.S.’s central bank and it controls monetary policy. Monetary policy covers a lot things that the bank can do as a lender to and regulator of the private banking system, but the biggest and most important policy is interest rates. Whatever the Fed sets as its interest rate is very influential of interest rates throughout the economy.

The Fed uses interest rates to manage household and business spending in the economy. When the economy needs less spending, the Fed raises rates, when it needs more, the Fed lowers them.

Say your car is stolen, or breaks down completely, and that tomorrow you have to go get a loan and buy a car. The size of your car payment will vary based on the interest rate you get. The car costs $40,000 and you had to borrow $20,000. If you borrowed $20,000 at 8% you’d have a much higher car payment than if you borrowed at 2%.

So if the Fed sets interest rates high, you’ve got a high car payment and the money that could have gone to a vacation or new clothes is now going to interest on the car. If it sets interest rates low, you’ve got a lot more cash to spend than you would have with the 8% loan. By manipulating the price of borrowing, the Fed has influenced spending in the economy.

You’ve lived through this in both directions.

The pandemic crash: get the economy going

When the pandemic took hold in March of 2020 and the economy shed over 20 million jobs in a single month, the Fed dropped interest rates to 0% and kept them there for about two years. The relief from Congress was much more visible—unemployment benefits, support for state governments, student loan forbearance, stimulus checks, money for food stamps, and so on—and meant to prop up households in crisis. The Fed’s policy is more subtle and less targeted: help anyone who has or needs debt by reducing their borrowing costs.

The US economy has four components that, when added together, equal the size of our economy (aka GDP).

Household spending

Business spending

Government spending

Net exports

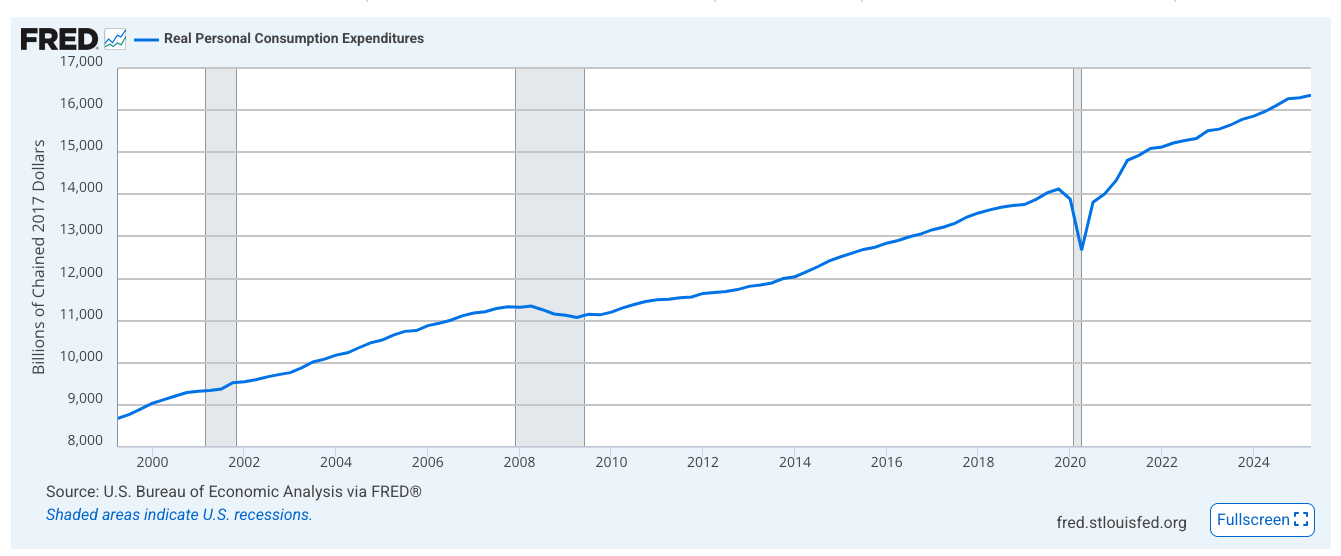

Household spending is BY FAR the largest component, typically around 65%. Keeping people spending is a way to stabilize the economy. Lowering interest rates helps juice spending. For reference, here’s consumer spending from the 25 years. You can see the difference between a small recession (2001), a large recession (2007-2009), and the pandemic (2020).

So:

Economy in trouble —> lower rates —> people have more money to spend —> spending boosts economy —> hopefully economy in less trouble.

The inflation spike: slow the economy down

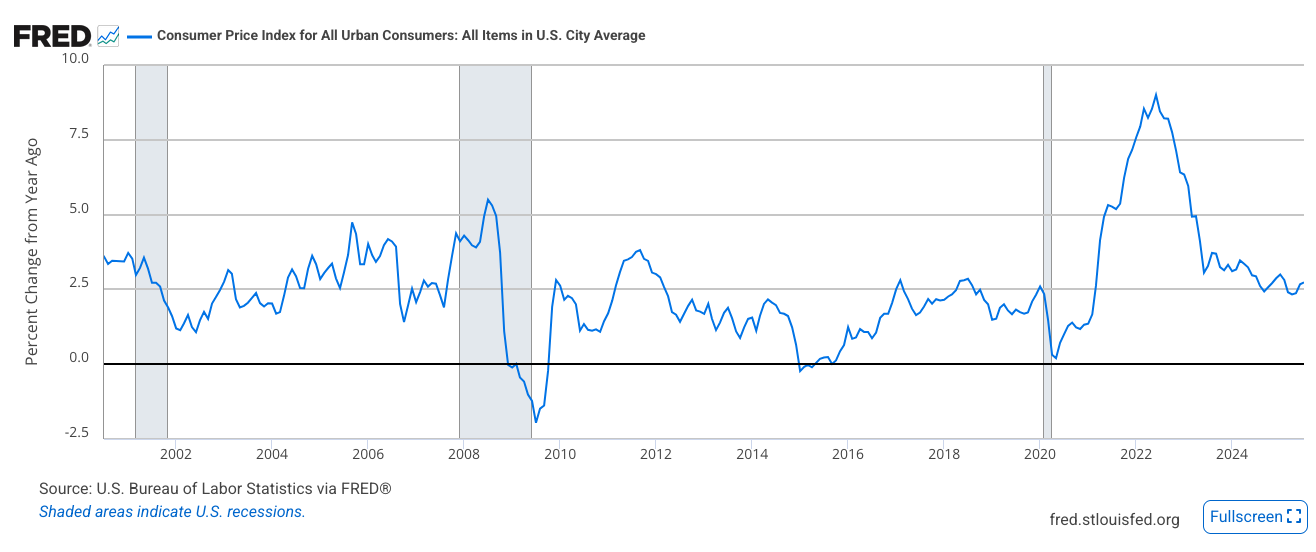

Inflation increased nearly every month in 2021. It started the year at 1.3% year-over-year growth but ended the year at 7.1%. You can see the spike in this chart, showing the inflation peak in June of 2022. For reference, the Fed’s target is to keep price growth at 2.0% year-over-year. (If you are wondering why it’s not 0% instead of 2%, I put in a post-script.)

At the start of 2022, the Fed raised interest rates and by the summer of 2023, interest rates were above 5%.

This hurts. And it’s meant to hurt. It’s again more subtle and less targeted: hurt anyone who has or needs debt by increasing their borrowing costs. Having less money to spend means spending less, and spending less puts downward pressure on prices, curbing growth.

Hang on you just said that consumer spending is most of our economy and now you’re saying that high interest rates reduce spending. Isn’t that bad???

Yes it is. In fact, most of the time in order to bring price growth down to target levels, spending pulls back so much that the US tips into recession. One reason why there’s been near constant speculation about the US entering a recession over the last two and a half years is because of that historical prediction. The hope from the Fed was that they could lower inflation and avoid recession, which they call “The Soft Landing.” It’s quite hard to pull off.

So:

Price growth too high —> higher rates —> people have less money to spend —> less spending hurts economy —> hopefully price growth falls —> hopefully there’s no recession.

It’s a real fingers-crossed-emoji economic era we’ve been living through, and all that was just the run up to the second Trump Administration.

Why Right Now is Confusing Part 1: The Actual Economy

By December of last year, it really looked like Powell and the Biden Administration had pulled off The Soft Landing. Inflation was falling, it was below 3% and on its way to 2%; GDP, consumer spending, and business spending were posting stable growth, and the unemployment rate was sitting around 4%.

Cracks were showing, though, especially in the labor market. The hiring rate cratered. People weren’t getting laid off, but they were having a hard time finding a job. The unemployment rate of young workers with less experience was ticking up. Wage growth also slowed.

The consensus at the start of this year was: so long as price reports keep showing inflation marching back down to 2%, the Fed would cut rates before the labor market got any worse.

And then, tariffs!

Tariffs raise prices. Put a tax on a good that is sold in the US or used for a good made in the US, and prices for both will increase. In fact, Trump made the big Rose Garden announcement of the new tariffs imposed on nearly every country we trade with on April 1—inflation has increased every month since.

And if that weren’t worrying enough, there’s reason to think that most of the tariff-inflation hasn’t even hit yet. Businesses have been trying to shield their customers from price increases—they’ve said so in surveys, in earnings calls, and in the meantime they stocked up on as much goods as they could before the April announcement. That can’t last. Prices will continue to go up, it’s just a matter of how high and for how long.

But the cracks in the labor market are also getting bigger, a lot bigger. The overall unemployment rate is ticking up a tiny bit while more groups within the labor market are experiencing visible pain through high unemployment, long lengths of unemployment, and still low hiring. Businesses have also said in surveys and earnings calls that layoffs may be necessary in the near future.

Beyond the direct impact of tariffs on prices and business operations, there’s a secondary impact of uncertainty. What will tariffs be when all the negotiation and showboating is done? When will those tariffs be set? Is a court going to invalidate all of this anyway? A lot of businesses are idling in place, just trying to hold steady while the tariff policy shakes out. That uncertainty is also dragging on the economy. If you can’t plan, you can’t grow, if you aren’t growing, you aren’t investing and you aren’t hiring.

So now for the $30 trillion question: what should the Fed do?

Option one: Prices come first. The full extent of tariff-inflation isn’t done or known. If the Fed lowers interest rates too soon and prices take off, it’ll have to raise rates again. The backtracking of interest rate policy is doubly harmful, not just because interest rate increases cause pain but the Fed loses credibility.

In sum, keep rates where they are and be ready to raise them.

Option two: Unemployment comes first. If the Fed waits much longer to cut interest rates, the labor market could decline enough to kick off a recession. All it takes is a few months of elevated layoffs for the unemployment rate to jump, businesses and households to panic in response and pull back further from economic activity.

In sum, give the economy some juice and lower rates ASAP.

The textbook prediction of tariffs is that they could cause stagflation, the unique and awful combination of high inflation with stagnated growth. One calls for higher interest rates, one calls for lower interest rates. We are seeing that play out in real time, ever so slowly. By all accounts, the Fed is waiting to see which one hits first and worst.

Why Right Now is Confusing Part 2: What Trump Says

Trump is his own worst advocate here, for pretty obvious reasons.

He wants interest rates lowered, immediately. He was returned to office on the promise of his economic management. A recession wouldn’t be good for midterms or his legacy. He wants rates cut so Americans get some relief.

Given what I explained above: if you wanted to make that case, you would use every microphone in front of you to talk about how weak the economy is right now and how precarious its current position is. In other words, you’d want to persuade the Fed that the first and worst problem is the labor market.

Trump can’t do that, because if the economy is weak right now, it’s entirely due to his own mismanagement and terrible policy of tariffs and trade wars. He wants the Fed to ease the pain that his own policies are causing without admitting that they are causing any pain.

So his tack is to 1) insist on every level that the economy is AMAZING thanks to the BEAUTIFUL tariffs while also 2) pressuring the Fed.

What happened in August is that these two prongs both reached a historical apex. The Bureau of Labor Statistics released in its monthly jobs report that job growth is low, even lower than was previously thought, a sure sign the economy is slowing down. This is probably the single most influential data point that you could hand over to the Fed to implore them to lower rates. Instead, he fired the Commissioner and said that the weak data was the result of her manipulating the report which she did for political reasons.

I cannot overstate how impossible that would be, how it is unequivocally and categorically not true, and how interfering with the independence of the statistical agencies risks so much more than a rate cut.

Then a few weeks later, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell gave a speech in which he said that tariff-inflation was just beginning and he didn’t know how high, how quickly, or how long prices would rise for. Within hours, Trump announced that he wanted to fire one of the Fed governors.

Interest rates are voted on by the Board of Governors. Trump is trying to get majority on the board to get the Fed to do what he wants, so if he fires a Governor, he can replace her with someone who will do what he says.

Again, I cannot overstate how interfering with the independence of the Federal reserve risks so much more than a rate cut. You can see it all here. Trump, like most politicians, want the economy juiced via lower rates so that people can spend money and are happy. Which is why whenever there is interference with a central bank (it hasn’t really happened here in the US though Nixon tried it to some degree, but its happened in other countries) the result is inflation. Politicians don’t have the stomach or the strength to look at economic data and know that the pain of higher interest rates is the only way forward.

Coda: There’s Always Hope

Listen, everything I just explained above augurs a future that promises inflation, recession, possibly both, and the loss of integrity at critical institutions regardless. But we can step back and see the real problem here: Congress.

If tariffs are hurting the economy, who could act to turn them off? Congress.

If critical independent agencies that produce economic data or use that economic data to maintain economic stability are under attack, who could guarantee that the leaders of those agencies serve the economy first, and not the president? Congress.

Sure, it’s not *inspiring* much. I don’t look down at this photo and feel more confident than I did before:

^Senator Majority Leader John Thune of South Dakota

The question isn’t “Will Trump’s policies harm the economy?” because they actively are. The question is, “How long will Congress allow him to do that before they intervene on the economy’s behalf?”

That’s a different answer, one with a lot of possibilities. It ain’t much, but it ain’t nothing.

P.S. Why is the price growth target 2%?

This can feel counterintuitive—wouldn’t we want price growth to be zero? Zero sounds nice but it’s too close to negative price growth aka deflation for comfort.

That also feels counterintuitive—wouldn’t it be good if prices fell? Again, sounds nice but it portends an economy in crisis and a ‘death spiral’ of spending that is associated with depressions as people wait to spend until they think prices have bottomed out, which pulls down the economy, we further drops prices, and so on and so on.

Put differently: we want prices to fall for the right reason, like a technological advance or a newly efficient supply chain. That happens to specific prices all the time! But falling because the economy is crashing and pulling down all prices as as result, that’s bad.

Also, keep in mind that 2% is a target, an outcome, and a signal.

Target: This is the rate of price growth the Fed wants to achieve

Outcome: A steadily, sustainably growing economy produces stable price growth.

Signal: The commitment to 2%, and hitting that mark most of the time, signals that our economy is well managed and that we have a strong, skillful central bank.

Finding someone who can explain US economics in such a clear, concise and comprehensible way is truly amazing. I needed this explanation in the worst way. Thank you. Experts in the field often fail to explain in ways that a novice can understand. Outstanding job.

You are so good at this kind of explainer-without-dumbing-down!

Just a query from my inner editor. A couple of times you say you cannot understate such and such. I think it should be “overstate”.