How worried should I be?

Layoffs in the US economy

The Musk/Trump team has been laying off federal workers. Of course, on brand for their total lack of transparency and accountability, we don’t know how many (though many outlets are trying to figure it out). Estimates are that because there are 220,000 probationary employees and there was an announcement that they had all been let go, the potentials is for that many, or more, to be gone.

I got a text from a friend who, like most of us, immediately equates news of layoffs with being in a recession. “How worried should I be?”

This newsletter is somewhat of a primer of layoffs and the labor market.

But first a quick disclosure: I find the denigration of civil service to be awful, and I am sad for these workers and our country. We are losing so much more than just jobs. However, this newsletter is going to talk about the economic dynamics in a clinical and somewhat cold fashion. It’s not because I’m not sympathetic or don’t see humans behind these numbers.

Layoffs are a Part of the Economy, All the Time

The US economy is very large. It has just under 159 million jobs in what we call ‘payroll employment.’ That’s exactly like it sounds, it’s the number of active jobs on the payroll of an employer. It could be part-time or full-time, could be seasonal or temporary (we count all of that separately too, but this is just to give you an idea of size). The labor market boasts 170 million workers, most of them in jobs, some in two jobs, some of them self-employed, some looking for work.

This massive market is always churning. Every month, people get laid off, quit, find a new job, switch jobs, retire, start looking for a job, stop looking for a job. Specifically:

Over the last three years, there was an average of 1.6 million ‘layoffs and discharges’ each month, which includes layoffs, fires, business closures, mergers, and the end of seasonal or term jobs. Basically, the person isn’t in the job, and they didn’t quit, retire, or die.

An additional 220k extra workers being laid off in a month is large, but it’s not catastrophic. Put differently: an increase in layoffs in a month does not mean a recession must come, or a recession is somehow unavoidable. That’s in part because:

Layoffs Don’t Always Reflect Overall Economic Activity

The federal employee layoffs will reduce the number of jobs in the economy. But that’s not “recession-ary” per se because it’s not signaling that the economy has taken a turn. On a mercurial whim, and motivated purely by power and retribution, these jobs were ended. That’s different from, the economy is so slow we could no longer afford staff.

Big layoffs that don’t reflect economic activity (and therefore don’t instill panic) can and do happen. The Census Bureau, for example, hired half a million people for the 2020 Census. The survey ended, so did the jobs, and it didn’t automatically usher in a recession simply because it was a large number (granted they weren’t all let go the same month, but you get the idea).

Another example is natural disasters. To be a job counted in payroll employment, it must be filled, paying, and present. Someone is in the role, being paid for work, and is at work. A natural disaster can sideline tens of thousands of workers because they aren’t at work, similarly reducing the number of jobs in the economy. But again, since it doesn’t reflect the real-time strength of the economy, it doesn’t indicate a recession and isn’t interpreted as a harbinger of one.

[[SIDEBAR: If you are curious how all this works, economic data is based on surveys that ask about a specific time period within a month. So you wouldn’t be asked, “Do you have a job?” you’d be asked “Did you work for pay for an employer the week beginning February 10th?” This is called the reference week and it is whatever week includes the 12th of the month. For this reason, the federal layoffs will likely not ‘show up’ in this month’s economic data because the reference week was the week leading up to the layoffs. We won’t see the total scope of layoffs' impacts on overall economic statistics until the first week of April, when the March data is released.]]

It is completely plausible that even with a high number of laid off federal workers, the economy is fine. It certainly doesn’t guarantee a recession.

That Said, Layoffs are Very Dangerous

What most people get wrong about recessions is that they assume they are characterized by layoffs, i.e. a recession is when a lot of people lose their job. But that’s just how recessions tend to start. What really characterizes a recession is hiring, i.e. a recession is when a lot of people can’t find a job.

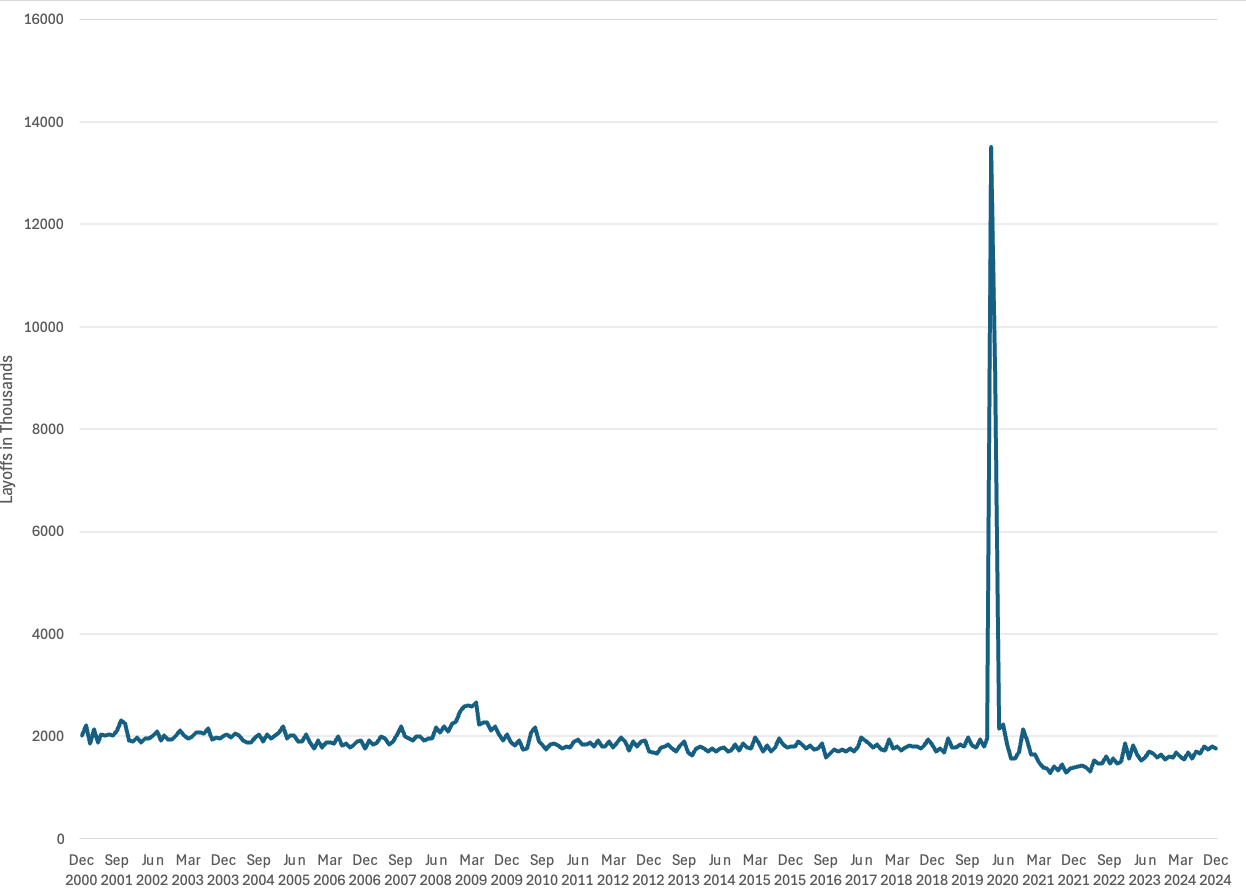

You can see this in the data. Here’s the number of layoffs and discharges in each month since 2000.

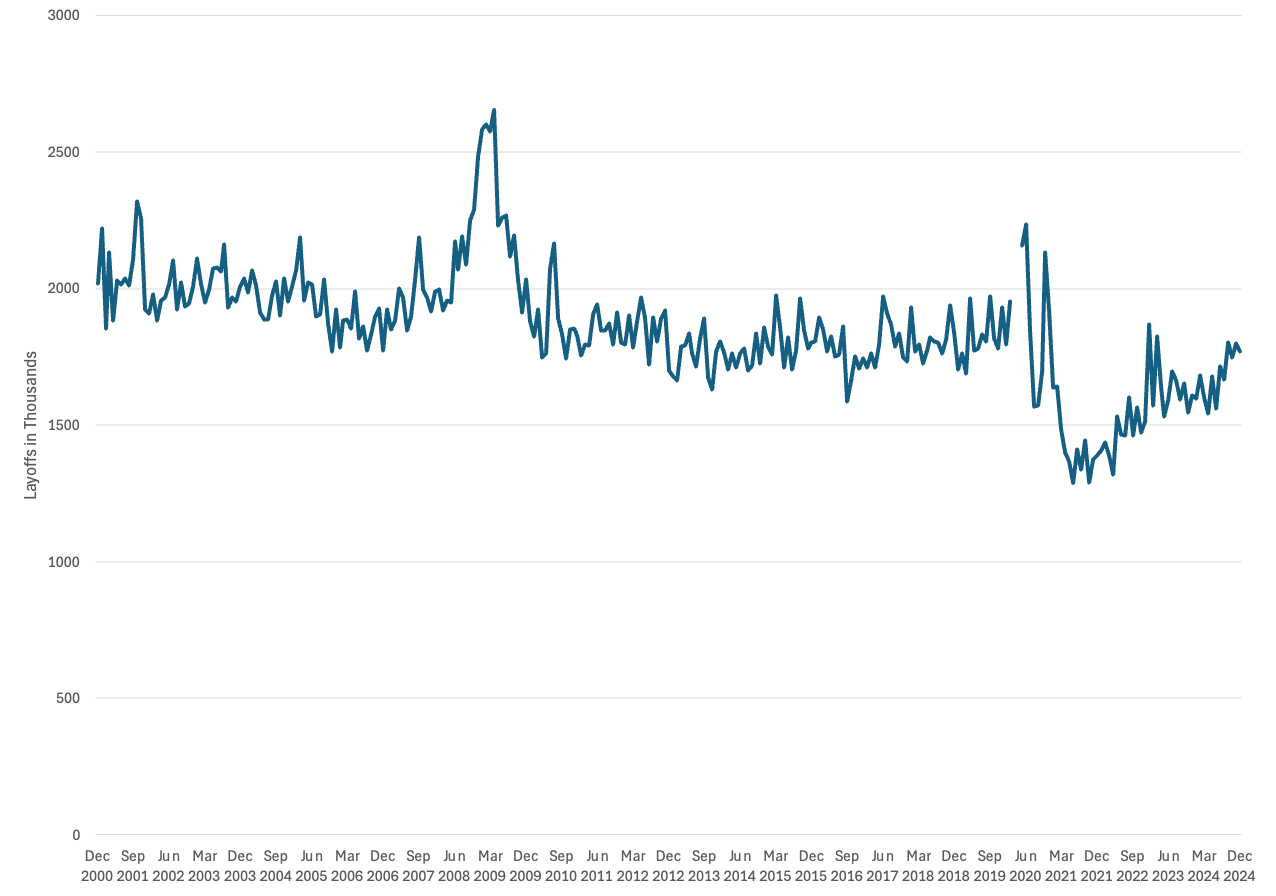

Obviously this chart is unreadable because of how drastic the pandemic layoffs were (13.5 million in March of 2020 and 9 million in April). I’m going to remove those two months of data so you can actually see something, I could just never present altered data without showing you unaltered data first.

Layoffs tend to be really stable. They jump up in recessions but that jump doesn’t last long. The 2007-2009 recession aka The Great Recession really only saw 5 months of very high layoffs before they dropped down to normal levels. It falls as fast as it rises.

That’s not true when it comes to hires. Here’s the number of hires in the economy over the same period (again with the 2020 spike removed so you can see the trend). Hiring fell below 5 million per month in March of 2008, when the economy was a few months into the recession. It continued to fall through June of 2009. It didn’t get back up to 5 million until the summer of 2014.

I overlaid these two data series and put them on separate axes so you can compare their shape side-by-side. They aren’t the same.

And of course, if you look at the tail end and the last few years, these lines are ‘heading towards each other’ again (it’s not actually towards each other because they are on different axes and hires is always much higher than layoffs, but you can see the direction and it ain’t great.) I wrote about recently how the fall in hiring is evidence of a labor market that is much weaker than it appears.

So the mechanics of a recession are: a lot of people are laid off, but they aren’t absorbed quickly into new jobs, increasing the unemployment rate. This reduces economic activity through:

1) direct channel: the people without jobs spend less

2) indirect channel: the people who have jobs see the high unemployment rate, worry that they’ll lose their job and spend less

3) feedback channel: both the increased unemployment and worry over unemployment saps workers of bargaining power, depressing wage growth and by extension spending power.

A jump in layoffs is danger territory for the economy because it’s how recessions tend to start. But, the real recession factor is how quickly they get hired back into work. It’s simply too soon to know how that will play out. It could be a blip. It could be a bump. It could be a jump. (All technical terms, mind you!) Either way, the largest employer in the US both shedding jobs and not hiring while the labor market is in a weak place—that’s playing with fire.

If you’re worried

The most important thing to remember is that recessions tend to tell us they’re coming. The pandemic was an exception to this because it wasn’t a result of the state of the economy, but the lockdowns. Most of the time, the economy gives us a lot of warning and that leaves room for policy to make a difference.

And while you might not have much faith in Congress or their motives, an economy spinning into recession within 12 months of Republicans coming to power—when they inherited a 4% unemployment rate and a mandate to help people struggling with the effects of inflation—is bad for them, and they know it. If nothing else, their political self preservation is aligned with a good economy. It’s not much but I’ll take it.

Thank you.

If layoffs reduce spending which reduces economic activity which could lead to a recession, then could an increase in spending lead to an economic boom? What should the Trump administration do if they wanted to layoff a bunch of government workers but also create a booming economy? Stimulus checks? Or for a more lasting effect, maybe raise the minimum wage?