Briefing: The Child Care Crisis

Part 3 What We Lose

Note, this is a series I’m doing about childcare in the US, motivated by the upcoming cliff in childcare funding. You can read Part 1 The Set Up to learn more about that and Part 2 The Bookends to understand the very challenging context of childcare policy.

What do we lose when we don’t have affordable care? That is, what don’t we have now compared to what we would have in a world with guaranteed access to affordable child care in the US, with capped costs for families? Today I’ll discuss

1 An Accounting of Loss

2 Would Be Children

1 An Accounting of Loss

There are four channels of loss from not having access to affordable and accessible childcare in the US:

Loss to children - early childhood programs are investments in their education, health, and development

Loss to moms - free or near-free care enables higher labor force participation and earnings

Loss to families - free or near-free care saves them money they would have spent themselves

Loss of children - the more expensive kids are, the fewer families have

The size of each of these losses is relative to the current state of the world and none of them are polar extremes, but often degrees. Starting with number one, the loss to children of the foregone investment in early childhood education. Many children have access to and participate in early childhood education programs today. The loss is from which children would participate who currently don’t or how participation would change. Same with moms. The majority of moms work. But how many more moms would work, or work more, or work in different jobs is the question.

From other countries, from limited interventions and programs within the US, we have a large amount of evidence to understand what these losses would be.

The two with the most evidence are #1 and #2: early education helps kids develop and putting kids in a safe, free place results in more moms working. That’s not to say all the evidence is in concert, but rather there is a textured evidence base that includes large effects, small effects, no effects, secondary effects in different places and setting that together provide us with a good understanding of what we can get if we do it right.

Here are some links for that: Tim Bartik’s book on early childhood education, a write-up in vox of DC’s pre-three program, an academic review of the relationship between labor and child care, a slam-dunk paper on why US women work less from the queen herself Fran Blau and guest, a Brookings report that makes a similar case, an Equitable Growth blog post making a similar case, a pretty blunt assessment from the National Association of Manufacturers about why they need child care, among many others.

#3 families would have more money is less a cause-effect so much as a mechanical result: if they didn’t have to buy care they could use that money for something else. Quesiton is, what is the result of families having more money? It’s probably good! We learned this from the 2021 temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit; if you give families with young children more money, they tend to spend it on necessities.

The poverty center at Columbia has a research roundup of all the good things that the expanded child tax credit did, touching everything from the mental health of parents to school supplies. It’s an interesting proxy for what not having to pay for childcare could do for families.

It begs the question—which is the largest loss? Which matters the most?

I’d put my money on #4 having fewer children. Whether I think about it as a cold bloded economist or a real human with feelings, families having fewer children than they would prefer is a loss we can’t count, which makes it the worst.

2 Would Be Children

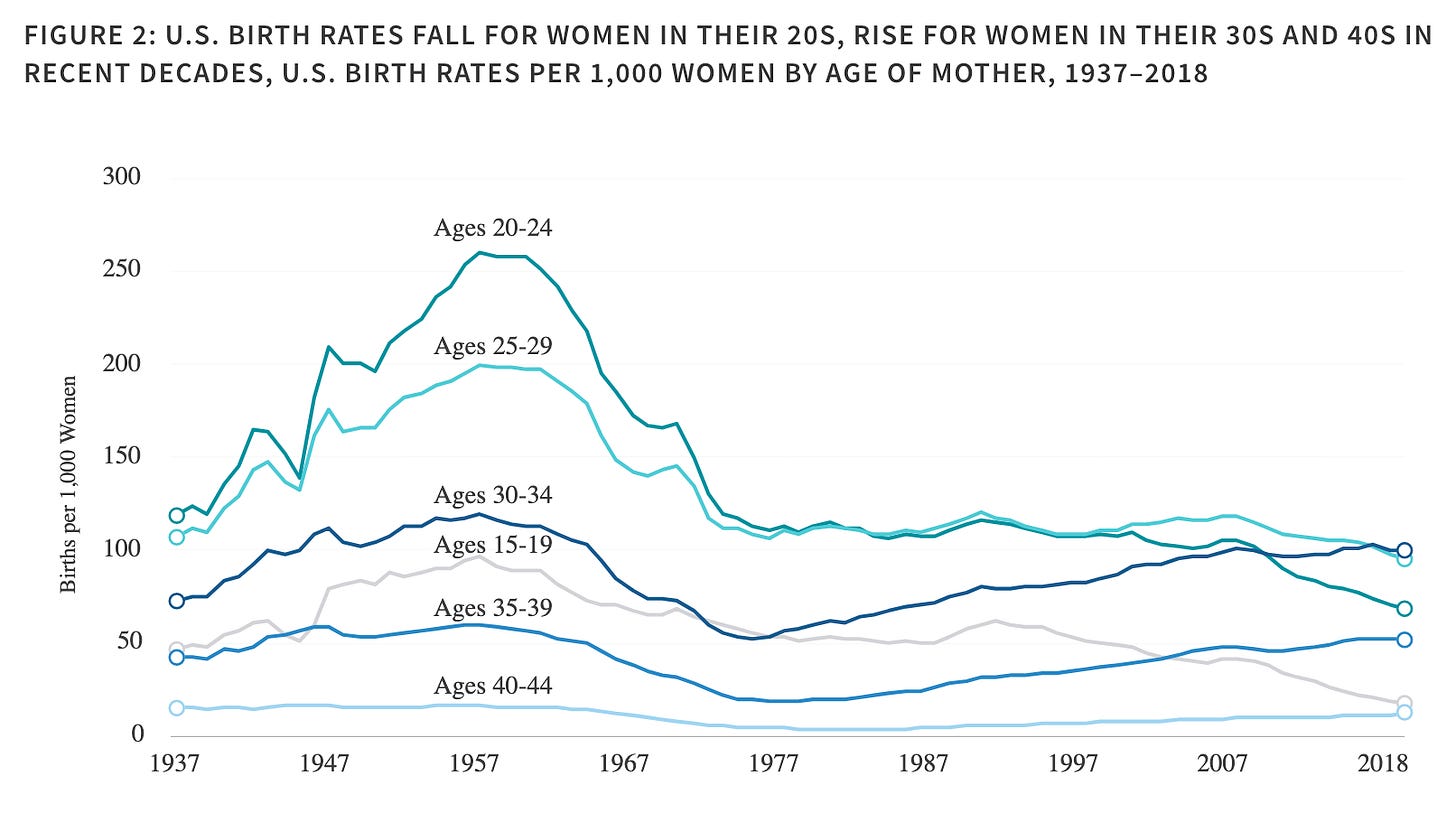

Fertility is declining in the US. Pew has a report that walks through fertility in each state, if you’re curious. For the US overall, it declined over the past thiry years from 71 births per 1000 women to 56 births. Or, the total fertility rate (the average number of children a woman has) dropped from 2.2 to 1.64 in 2020, which is below population replacement. You can see in the figure that the decline started with the Great Recession, but didn’t recover.

Some of what drives the decline over this period and historically is a reduction in teen pregancies—that’s also pushed up the average age at which women first have kids.

This figure makes it clear: fertility has dropped a lot for women under 30 and increased for women over 30. But the drop is larger than gain, so it’s a net decline.

There’s a lot of speculation about what’s going on. And since the would be moms right now are mostly Millennials (like me!), there’s also a lot of awful essays and takes about what’s wrong with us personally—we’re immature, we’re not independent, we’re not as good as the boomers, we want different things, whatever whatever whatever—and discussions of cultural causes.

But a really fascinating study came out earlier this year that examined fertility intentions across cohorts over time (cohort=people born in the same year or set of years) (because generational labels like Millennial are a pop phenomenon and not a real thing, researchers look at cohorts) (the more you know!!!!!). They use the National Survey of Family Growth to look at 1) how many kids different cohorts said they wanted and 2) how many kids they actually had.

What they found is that people today want the same number of kids as earlier cohorts—about two kids. And there is a pretty stable share of people who never intend to have kids, around 15%. What’s happening is an “intention gap” or a “fertility gap” where people haven’t had the number of kids they wanted by the time they age out of childbearing.

Lower fertility isn’t a result of preferences, but constraints.

(The cultural causes can still be happening, or, the motivations behind the intending to be childless can be more cultural than they were previously).

But this—that women are having fewer children than they want—is a big finding.

Bringing it back to childcare, I want to show this jaw-dropping poll that the Morning Consult and New York Times did in 2018. They asked people about their fertility intentions and identified a set of people who responded that they were going to have fewer kids than they thought was ideal. Of those, they then asked why they were going to have fewer than they wanted. It’s stark.

They were allowed to pick more than one, which is why these numbers don’t add to 100, but it’s nonetheless incredible to consider that two-thirds cited childcare costs. Keep in mind that the maximum amount of time you have to pay for childcare is five years. It’s a temporary cost. And yet it’s so considerable it’s the most cited reason for having fewer children.

The American Compass has done other surveys where they ask about the state of the American family and they’ve noted, in a way that makes a lot of sense, that the cost constraint is more likely to be report by lower-, working-, and middle-class Americans (those are their descriptors) and it’s the upper-class who stop having kids for career or lifestyle reasons. Not for nothing is paid leave mention by just under 40% of respondents in the Times graphic.

There’s the coldblooded economist in me that sees this through the policy lens—what an easy and well motivated intervention. People want more kids. We want people to have more kids. They say childcare is a big problem. Boom. We know what to do!

But I also find it so stupid and so sad that we even have to collect evidence like this to motivate paying for childcare.